In the evening of the 26th November 1939, Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Armas Aarno Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen, received a note from Soviet Foreign Minister Vjatšeslav Mihailovitš Molotov. It read:

“Monsieur le Ministre,

According to information received from the headquarters of the Red Army, our troops posted on the Carelian Isthmus, in the vicinity of the village of Mainila, were the object to-day, November 26th, at 3.45 p.m., of unexpected artillery fire from Finnish territory. In all, seven cannon-shots were fired, killing three privates and one non-commissioned officer and wounding seven privates and two men belonging to the military command. The Soviet troops, who had strict orders not to allow themselves to be provoked, did not retaliate.

In bringing the foregoing to your knowledge, the Soviet Government consider it desirable to stress the fact that, during the recent negotiations with M. Tanner and M. Paasikivi, they had directed their attention to the danger resulting from the concentration of large regular forces in the immediate proximity of the frontier near Leningrad. In consequence of the provocative firing on Soviet troops from Finnish territory, the Soviet Government are obliged to declare now that the concentration of Finnish troops in the vicinity of Leningrad, not only constitutes a menace to Leningrad, but is, in fact, an act hostile to the U.S.S.R. which has already resulted in aggression against the Soviet troops and caused casualties.

The Government of the U.S.S.R. have no intention of exaggerating the importance of this revolting act committed by troops belonging to the Finnish Army – owing perhaps to a lack of proper guidance on the part of their superiors – but they desire that revolting acts of this nature shall not be committed in future.

In consequence, the Government of the U.S.S.R., while protesting energetically against what has happened, propose that the Finnish Government should, without delay, withdraw their troops on the Carelian Isthmus from the frontier to a distance of 20-25 kilometres, and thus preclude all possibility of a repetition of provocative acts.

Accept, M. le Ministre, the assurance of my high consideration.

People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR V.] Molotov.

November 26th, 1939.”

The note made the veteran diplomat worried and confused. He immediately started to make communications with Helsinki in order to find out the truth and how to proceed. With tensions already high due to the ongoing negotiations between Finland and the Soviet Union, such an incident could spiral out of control and cost Finland her sovereignty.

The Incident

At the Russo-Finnish border near the Soviet village of Mainila, the Finnish Border Guards of 4th Border Guard Company were doing their normal duties for the day. They knew about the negotiations going between their Government and the Soviet Government, they knew that the situation was tense, but none of them could guess that it would only be a matter of days before all out conflict would erupt along the border.

The crisp air had brought the temperatures to just below freezing and winter was on its way. Suddenly at 1445 (Finland is an hour behind the Soviet Union) the stillness was disturbed by the thump of artillery, followed by another and another, explosions could be heard as the shells landed. Some of the Border Guards even witness the fall of shot and noted that soon a group of Soviet soldiers came up to inspect the destruction and promptly left soon after. It wasn’t much later that the Border Guards then reported a smoke screen going up behind the village.

As per protocol, the commander of the Guards sent a telegram to headquarters reporting the shots but as far as they believed, it was some kind of training exercise.

Diplomatic Back and Forth

Upon receiving Molotov’s note, Yrjö-Koskinen immediately got in contact with officials in Helsinki to inquire upon the incident. General Nenonen, commander of the artillery, confirmed that there was no artillery capable of shooting across the border, in accordance with Marshal Mannerheim’s orders and the Border Protocol between the two nations, which forbid the locating large units and heavy weapons close to the border. With the information provided by the Border Guards and confirmation by Nenonen, Yrjö-Koskinen presented a reply on the morning of the 27th November which recalled the Border Guards observations and that there was no Finnish artillery within reach. The note also said that Finland was willing to withdraw their troops from the border, so long as the Soviet Union did likewise. An appeal to the 1928 agreement on Border Guards for a joint investigation was also included.

The Finnish reply was met by a stiff retort from Molotov on the 28th. It opened by calling the Finnish letter a confirmation of ‘deep hostility towards the Soviet Union’ and lays the accusation that it ‘leads to an extreme escalation of relations between the two countries.’ It continues with the aggressive tone by stating that the denial of the shelling is a Finnish ploy to turn public opinion in their favour and that by refusing to remove troops from the border, Finland is a threat to the Soviet Union and the citizens of Leningrad. It states how the Soviet Union will not pull their troops back and justifies this as the Red Army is of no threat to Finland and to pull their troops back would put them within ‘the suburbs of Leningrad’. It ends by stating that Finland’s hostility towards the Soviet Union shows a lack of respect for the 1934 Non-aggression Pact and now it ‘feels compelled to declare that it will henceforth be free from the obligations ‘of the Pact.

This rather alarming turn of events worried the Finnish Government and on the 29th, Yrjö-Koskinen was ready to present another reply to Molotov and the Soviet Union. It opened by standing firm that Finland had not violated the ‘territorial integrity’ of the Soviet Union and repeating the appeal for a joint investigation by Border Guards on both sides. He also confirms that only Border Guards are deployed at the border and that they are not a threat to the Soviet Union. It continues with Finland’s rejection of the Soviet Union’s renouncing of the 1934 Non-aggression Pact on the grounds that there is no conditions to justify a right of termination before the Pact is up in 1945. This is followed by referring to Article 5 of the treaty and how both nations have promised to solve any disputes through peaceful means and that a special conciliation commission be set up in order to resolve this incident quickly.

However, before this letter could be delivered, Yrjö-Koskinen received a very short and curt note from Molotov. It alleged that other incidents had occurred along the Soviet-Finnish border and that as a result, while stressing that Finland is the only one at fault, the Soviet Union has no choice but to cut all ties with Finland.

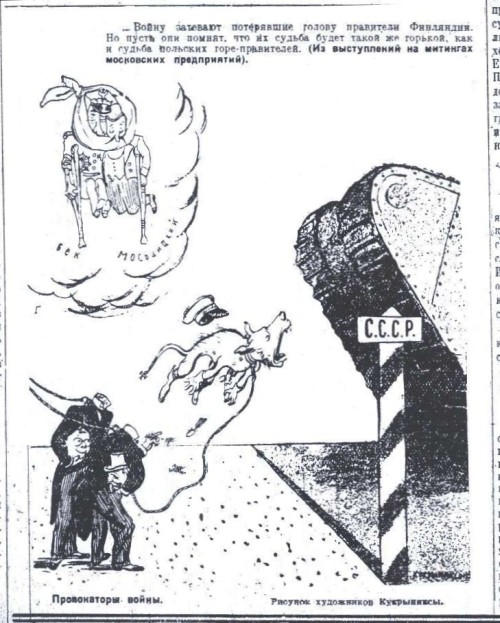

While this was going on, the propaganda machine in the USSR was in full swing. The day after the incident saw anti-Finnish demonstrations break out in Leningrad and by the 28th these had spread across the country. There were several radio broadcasts that pushed the narrative of Finnish aggression against Soviet Border Guards and the newspapers published stories of the horrible conditions that the Finnish peasant was subjected to.

Conclusion

The incident was used as the casus belli for the Winter War by the Soviet Union. The convenience of an unprovoked attack on Soviet soil allowed the USSR to keep up their pretense of legalism. However, similar to the Gleiwitz incident, the international reaction was mainly one of skepticism. The refusal of a joint investigation and the following conflict meant that any study of the incident occured and despite its pivotal role in the road to war, the Shelling of Mainila faded into the background.

The position of the Soviet Union remained steadfast the Finns were the cause of the shelling. During the Stalin years, the original story of it being an unprovoked Finnish attack was upheld. When Winston Churchill wrote his epic ‘The Second World War’ series, he recalled a conversation he had with Stalin at the Yalta Conference. While eating dinner, Stalin started talking to Churchill about past events, “The Finnish war,” he said, “began in the following way. The Finnish frontier was some twenty kilometres from Leningrad [he often called it “Petersburg”]. The Russians asked the Finns to move it back thirty kilometres, in exchange for territorial concessions in the north. The Finns refused. Then some Russian frontier guards were shot at by the Finns and killed. The frontier guards detachment complained to Red Army troops, who opened fire on the Finns. Moscow was asked for instructions. These contained the order to return the fire. One thing led to another and the war was on. The Russians did not want a war against Finland.”

However, this didn’t mean that some people didn’t swallow the story whole. Nikita Khrushchev (who at the time was a Commissar and served as an intermediary between Stalin and the Generals of the Red Army) claimed in his memoirs that the incident was set up by Marshal of Artillery Grigory Kulik. However he was coy about who fired the first shots and is quoted as saying “It’s always like that when people start a war. They say, ‘You fired the first shot,’ or ‘You slapped me first and I’m only hitting back.’ There was once a ritual which you sometimes see in opera: someone throws down a glove to challenge someone else to a duel; if the glove is picked up, that means the challenge is accepted. Perhaps that’s how it was done in the old days, but in our time it’s not always so clear who starts a war.”

It wouldn’t be until the fall of the Soviet Union, and the opening of the archives, that serious investigation of what happened at Mainila would take place. M. I. Semiryaga is generally cited as the first Russian historian to cast doubts upon the official story. In 1990 he wrote of the incident, ‘Of course, investigating such incidents committed by experienced provocateurs is a very complicated matter, but it must be carried out in hot pursuit’. Pavel Aptekar set out to solve the matter by analysing all records he could in regards to the incident. He discovered that the 68th Rifle Regiment of the 70th rifle division was assigned to the Mainila area but unfortunately its records appeared lost. However a small military log was found and the words “The location of the regiment on November 26, 1939 was subjected to provocative shelling of the Finnish military. As a result of the shelling, 3 Red Army soldiers and commanders were killed and 6 wounded.” were found on the first page. However discrepancies were found, the 25 page notebook was all signed by Captain Salynin, regiment commander, and Senior Lieutenant Knyazev, chief of staff. The regiment commander at the time was Colonel Korunov and his chief of staff Captain Rusetskiy. Upon further investigation, the records of the whole 70th Rifle Division showed no military or non-combat losses at the time of the incident. They also showed no information about the shelling, nor any records of Finnish artillery or large movements of troops.

Boris Yeltsin, the First President of the Russian Federation made a statement in 1994 denouncing the Winter War as a War of Aggression. However, it seems that in recent years, the incident at Mainila has been brushed off or outright ignored by Russian Politicians and Historians.

Finnish historians have also gotten in on the investigation. Jari Leskinen found information regarding Soviet War Games held in 1938 and 1939 were based around border incidents that had occurred in Mainila. Ohto Manninen found information in the archives of Andrei Zhdanov that hinted that the incident was orchestrated and that several commanders of the Leningrad District was given awards shortly following the incident.

While there is no smoking gun evidence, there certainly is enough evidence to draw the conclusion that the incident at Mainila was conducted by the Soviet Union in order to justify their invasion of Finland on the 30th November 1939.

Sources

https://web.archive.org/web/20190530224726/http://www.rkka.ru/analys/mainila/mainila.htm

https://histdoc.net/historia/historia.html

Edwards, Robert. White Death: Russian War on Finland 1939–40 (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2006)

Trotter, William R. The Winter war: The Russo-Finnish War of 1939–40 (Workman Publishing Company, 2001)

This is a great start ! I am going to read all of these with great interest ! Good luck with this !

Thanks Lyonel. You know how much I value your opinion and support.

Nice work!

Thank you Jakob